Introduction #

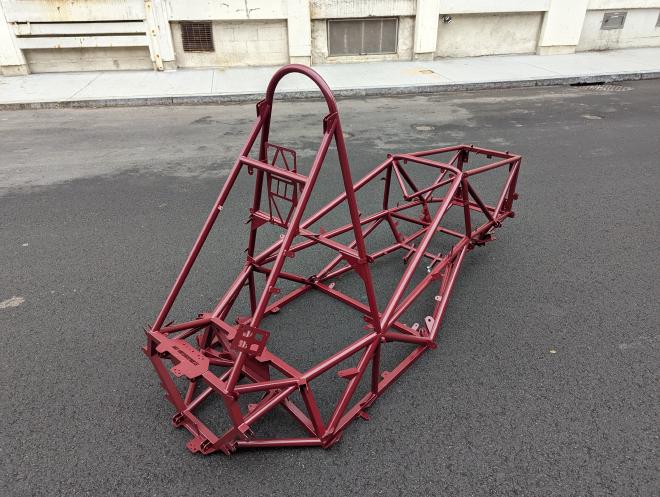

As chassis lead for MIT Motorsports, I was responsible for designing and building a steel space frame as well as leading a team of 12 to build the impact attenuator, firewall, seat, pedalbox, and steering wheel. I got the frame built faster than ever in our team’s history - typically we weld tabs throughout the spring semester and send it out for powder coating in May, but under my leadership the frame team was able to get the frame powder coated in early February. Additionally, the measured torsional stiffness (2000 +/- 80 Nm/deg) was more than double the measured torsional stiffness of our 2023 car, exceeding our design requirement of 1900 Nm/deg. I justified the torsional stiffness requirement using a springs-in-series model to quantify the diminishing returns on suspension compliance due to frame deflection.

The design is thoroughly documented in the following files:

I compiled pictures and videos from the whole year of motorsports in the following recruiting montage:

Literature #

I found the following to be the most valuable literature for designing the frame:

- Race Car Vehicle Dynamics by Milliken and Milliken (RCVD)

- Bill Riley’s Design, Analasys, and Testing of a Formula SAE Car Chassis

- The Effect of Chassis Stiffness on RaceCar Handling Balance